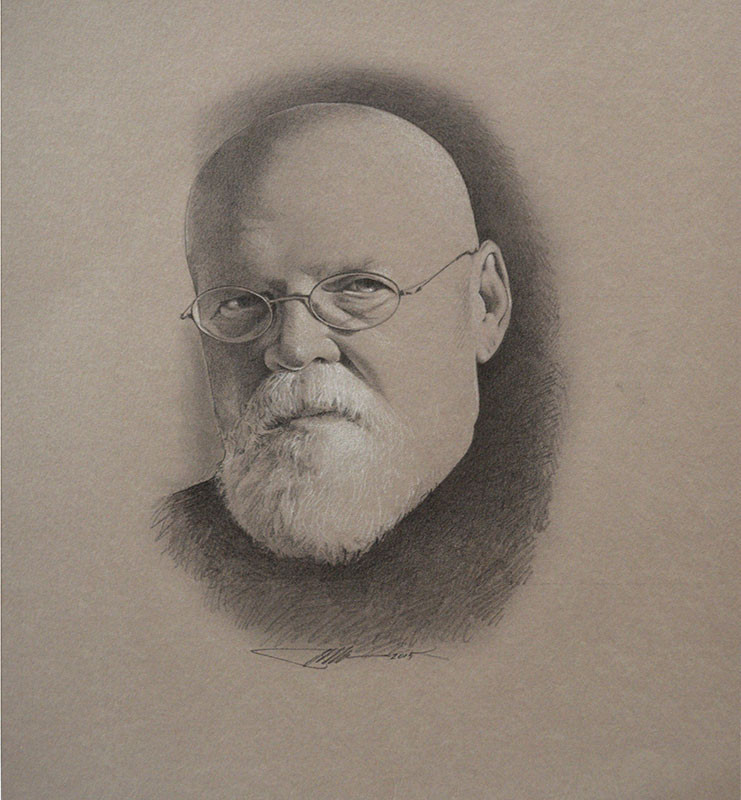

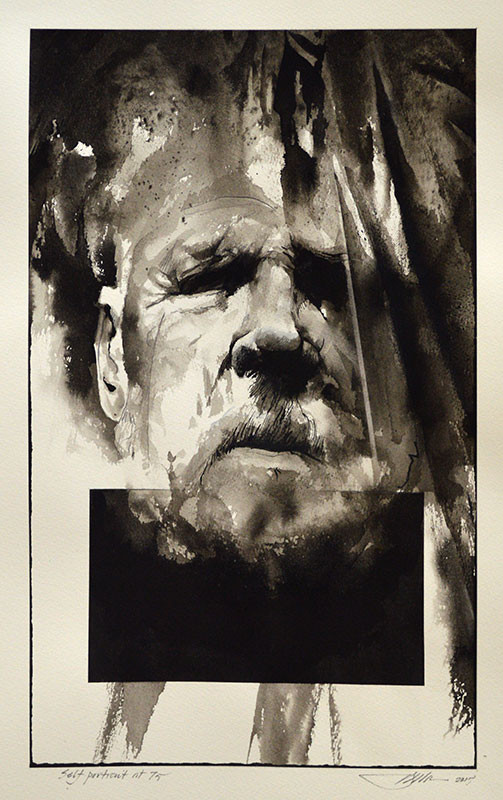

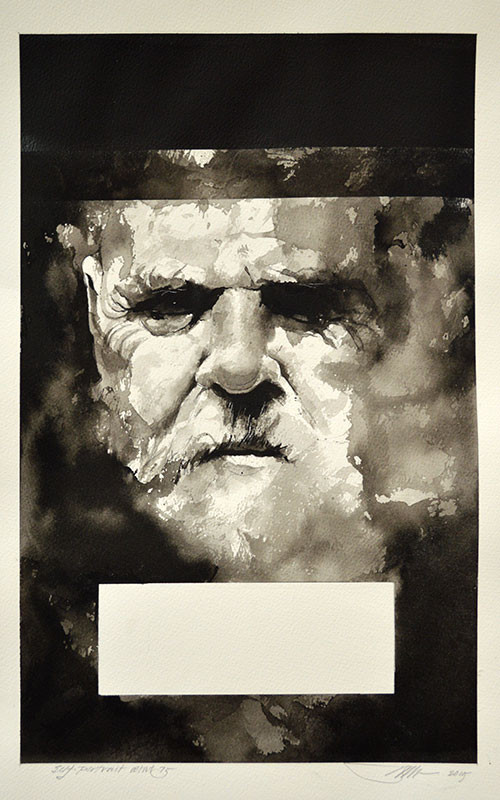

Barry Moser: Moser at Seventy-Five: New, Recent, & Unexpected Works

8.5×5.5 in

Barry Moser has a staggeringly significant body of work as a wood engraver, a watercolorist, and as a book designer. From his Pennyroyal Press fine art books, to his career as an illustrator of children’s literature, to the signature achievement of his Pennyroyal-Caxton Bible he has made an indelible mark on 20th-century illustration. In October of 2015, at the milestone birthday of 75 – and with his memoir, We Were Brothers soon to be released – he reinvented himself with this body of work. This collection of abstract works from one of America’s most celebrated realists is energetic and fresh and, as the title suggests, totally unexpected. Read The Artist’s Comments Regarding This Exhibit and listen to Rich Michelson and Barry Moser discuss the show.

17.25×10.5 in>br>SOLD

16.25×10 in

SOLD

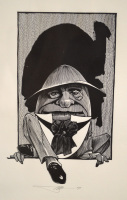

One could trace Moser’s entire career just by his self-portraits. There is one in nearly every book. To name a few: The March Hare in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a munchkin in The Wizard of Oz, Professor Atheist in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and a deceased Goliath in The Holy Bible. As an actor puts on a persona for a role, Moser inserts himself (as well as other notable and recognizable people) into the narratives.

4.25×5 in

4.5×5 in

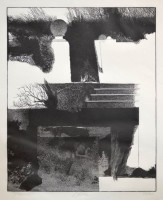

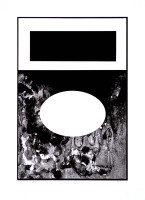

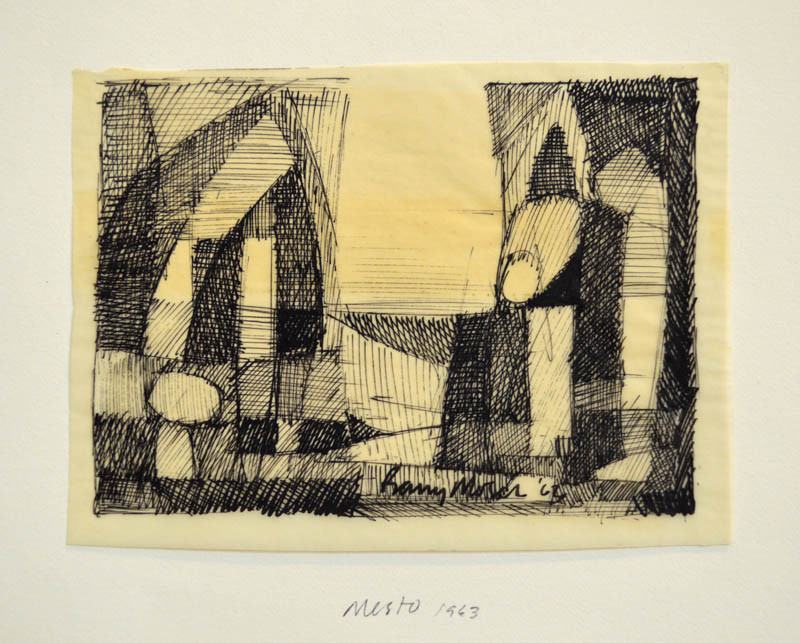

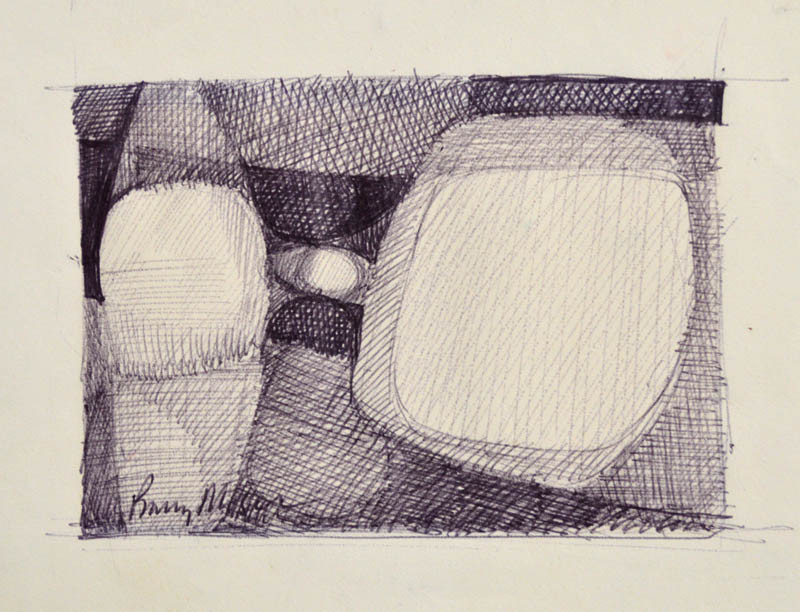

In the early 1960s Moser transferred from Auburn University to the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and studied under abstract expressionist painter George Cress. Cress challenged Moser to forsake his realist tendencies and to work solely on abstraction. These early drawings show some of the work of this time. He developed a fascination with architecture and breaking scenes down to simple shapes.

7.5×10 in

7.5×10 in

6.25×7.75 in

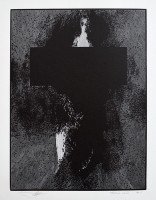

“I contend that all art is abstract. The essence of art, it seems to me, comes from conflict and resolution, or, put another way, from the tensions that exist between opposites-and subject matter has not a damned thing to do with it.” – B.M.

7×5.25 in

12×9.5 in

6×3 in

12×9.5 in

SOLD

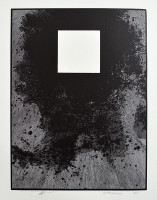

“…all art is a matter of contrast: push & pull, black & white; large & small; tragic & comedic; simple & complex; concave & convex. It is my job, as it is for any serious artist, to bring these disparate elements into balance and harmony” -B.M.

12×9.5 in

SOLD

4×3 in

SOLD

8.25×6 in

SOLD

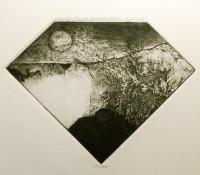

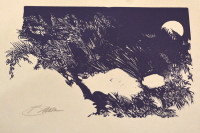

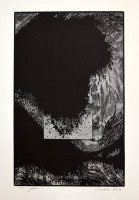

In the early 1970’s Moser produced a number of overgrown gardens teeming with mystery and excess. This time period saw the publication of his Pennyroyal Eight Wood Engravings on a Theme of Pan, and Bacchanalia, as well as a number of broadsides on the subject. Many of these played with abstraction to give a heightened sense of the fantastic. These and other works of this time jumbled the tangible with the intangible in a wonderful fashion. Of these early etchings, his large 1974 Treehouse is the most unique, blending numerous self-portraits with organic and geometric shapes.

7.75×8 in

7×9.5 in

4×7 in

4×6 in

22×12.25 in

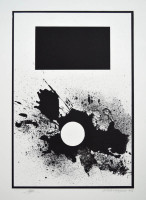

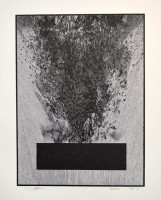

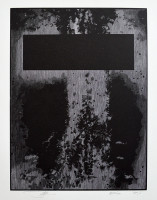

The abstractions are all titled with musical terms further confounding the viewer in extracting meaning. In his artist statement, Moser invokes Whistler. If people “could care for pictorial art at all, they would know that the picture should have its own merit, and not depend on dramatic, or legendary, or local interest . . . as music is the poetry of sound.”

19×15 in

19×13 in

12×9 in

13×9.75 in

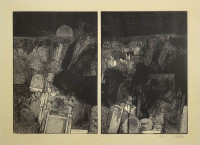

Moser always had a fascination with cemeteries and gravestones. Toward the late 1970’s and early 1980’s he renewed his fascination with architectural shapes. While these works are unrelated, they illustrate his ability and penchant to use abstraction.

9.25×4 in

12.5×9.75 in

7.5×10.25 in

7.25×5 in

27×20 in

22.5×17 in

23×16 in

21.5×15 in

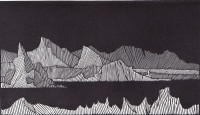

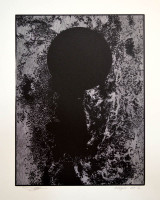

Even for books as tangible as Frankenstein, Moser broke scenes down to their most basic shapes as for the snowy wilderness that the creature escapes to in Arctic Landscape and a Richard Nixon-like Humpty Dumpty’s suggestive shadow.

3.5×6 in

9×18 in

9×6 in

Click image to view video

25×20 in

24.25×18.5 in

21.5×17 in

24.25×18.5 in

22×14 in

SOLD

18×9 in

SOLD

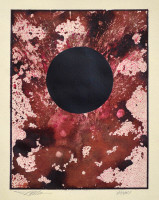

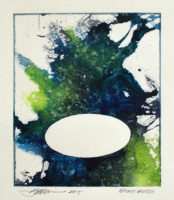

Throughout his career, while still firmly rooted in realism, Moser used abstraction to convey emotion and illustrate the intangible. The first of these, pictured below, is from his 1992 Messiah: Wordbook for the Oratorio and he used the same idea for his 1999 The Holy Bible. The third is from his children’s book on God, The Dreamer. and the fourth is to illustrate Henry Treece’s fanciful poem, The Magic Wood.

7.5×6 in

11.5z7.25 in

11×17.25 in

8.5×19.25 in

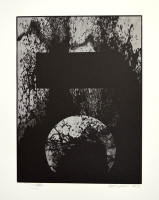

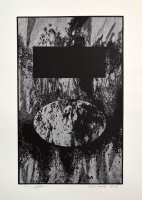

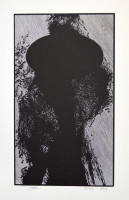

Lithographs

19.5×13 in

17×11.5 in

16.5×11 in

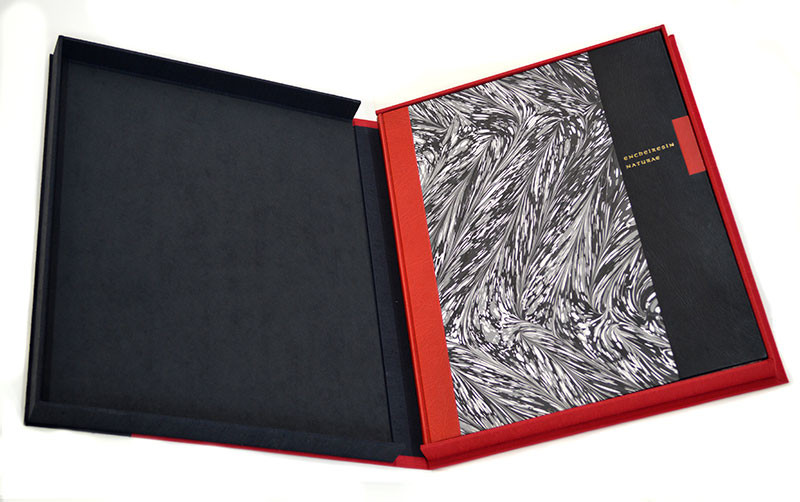

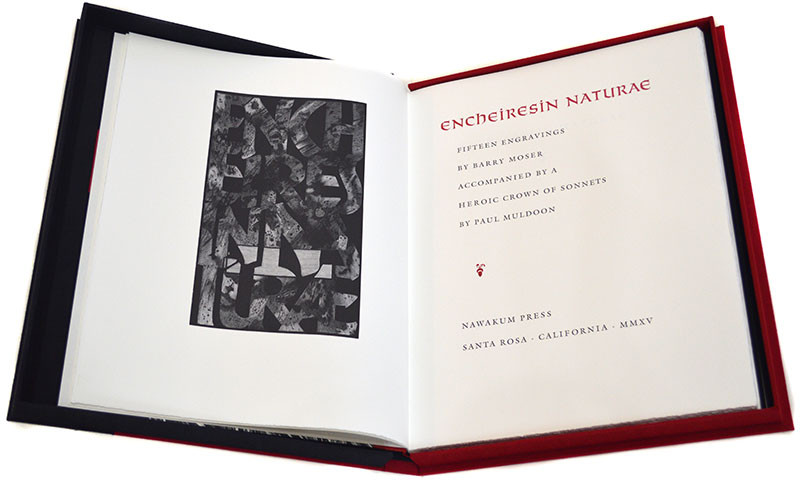

Encheiresin Naturae

A creative collaboration between Barry Moser and Paul Muldoon, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Irish poet published in a special fine press edition of fifty copies by the Nawakum Press and printed by Art Larson. The title for this new edition comes from Goethe’s Faust and is a specific alchemic term, half Greek, half Latin that suggests a manipulation or handling of Nature. Moser created fifteen exquisite relief engravings and Muldoon penned a heroic crown of sonnets, also known as a sonnet redoublé, to accompany them.

12.5×9 in

12×7.5 in

12.25×7 in

12.5×9 in

12×7.25 in

12.5×9 in

12.5×7 in

12.5×9 in

12.5×9 in

12×7.25 in

12.5×9 in

12.5×9 in

12.5×9 in

Paul Muldoon has been described by The Times Literary Supplement as “the most significant English-language poet born since the second World War.” Muldoon is the author of twelve major collections of poetry, and he has published criticism, opera libretti, children’s books, song lyrics and radio and television drama. In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, Muldoon has received an American Academy of Arts and Letters award in literature, the T. S. Eliot Prize, the Irish Times Poetry Prize, the Griffin International Prize for Excellence in Poetry, the Shakespeare Prize, the European Prize for Poetry, and many other awards. He has taught at Princeton University since 1987 and he is the poetry editor of The New Yorker. See the Pulitzer Prize winning poet discuss “difficulty” in poetry and his collaboration with the artist Barry Moser.

See more work by Barry Moser